I laid me down on Christmas Eve

And soon lay deeply sleeping.

Nor could I waken

Before the people went to church

Upon the thirteenth day.

The moon shone bright

And all the paths led far away.

—from “The Dream Song of Olaf Åsteson”1

Many of us in the English-speaking world are familiar with the carol, “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” Growing up without any knowledge of the liturgical year, I always assumed that the twelve days in question were those that came before Christmas. It’s not hard to see why I thought that—with holiday decorations and music appearing in the stores by early November, most people are done celebrating by Christmas night.

The Church takes a very different view of the situation. Advent marks the start of the Church year and is a season unto itself, beginning around the end of November and concluding on Christmas Eve. The Christmas season comes after Advent and lasts until Epiphany (January 6th)—and those are the twelve days of Christmas. Let’s take a closer look at what makes this time of the year so special, and why it is important that we reclaim it and explore ways to make it meaningful again.

Sun Year, Moon Year

Since ancient times, the days around the winter solstice have held important spiritual, religious, or cultural significance, as we see in the German “Smoke Nights,”2 legends of the Wild Hunt,3 4 or the folk tradition of making predictions about the coming year’s weather based on what transpires during the twelve days of Christmas.5

These days were not chosen at random; there’s a cosmological reason for their importance. The lunar year and the solar year are not a perfect match for one another. The lunar year, or twelve full cycles of the moon, takes about 354 days to complete. The solar year, or the time it takes for the Earth to orbit the sun, is about 365 days. This discrepancy means that the lunar year ends about 11 days—or 12 nights—before the solar year is complete. This gap is sometimes known as the “time between the years,” or Twelvetide.

Yearning for Stillness

What we have lost in our culture’s premature celebration of Christmas is not just the season of Advent, but a particular time of stillness in the Earth’s yearly cycle that comes after the feast, and to which the human soul yearns to respond. Just as a seed lies resting in the soil, awaiting a time of new growth, the human soul also feels moved to turn inward and dream about the future—there is a remnant of this instinct in the tradition of declaring New Year’s resolutions.

So, what can we do with these twelve holy nights? We can slow down, reflect on the year that has passed, and look toward the year that lies ahead, just as our ancestors might have done long ago. Living in a culture that values efficiency and expediency above all else, setting aside twelve days or nights to sit in stillness with one’s own thoughts is a truly revolutionary endeavor.

Ideas for Observing the 12 Holy Nights

Here are a few “themes” and activities that you might take up during the twelve holy nights this year:

Signs of the Zodiac

[Editor’s note: For a more in-depth exploration of the relationship between Christianity and astrology, you can read my essay Astrology :: A Faithfully Catholic Perspective]

As far back as the Middle Ages, the days between Christmas and Epiphany were seen as a time for making predictions about the coming year. Typically, each day of Twelvetide was associated with a month of the year, starting with January. Because the months were also strongly linked with their astrological signs—you can see this illustrated in medieval cosmological diagrams—each of the twelve days of Christmas could also be associated with one of the constellations of the zodiac.

You could draw, paint, or print out pictures of the twelve astrological signs and learn about their qualities, one each night starting with Capricorn. Research how the skies looked when you were born, to determine which heavenly bodies might have made an impression on you. Find a book with high-quality images of the sun, moon, and planets and learn about their composition and climate. Winter offers a clear view of the sky, so go outside and look at the stars. See if you can identify any constellations—Orion is an easy one for kids to spot.

You could also listen to classical music inspired by the sun, moon, and planets. Here’s are a few recommendations:

- The Planets, Op. 32: 1. Mars (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 2. Venus (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 3. Mercury (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 4. Jupiter (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 5. Saturn (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 6. Uranus (Holst)

- The Planets, Op. 32: 7. Neptune (Holst)

- Pluto, the Renewer (Matthews)

- Pan Voyevoda, Op. 59: III. Nocturno (Rimsky-Korsakov)

- Helios Overture, Op. 17 (Nielsen)

Labors of the Months

The medieval motif of the labors of the months offers a glimpse into a way of life that is rooted in agriculture and the seasons of nature. You can download beautiful, high-resolution images of the Labors of the Months from the Tres riches Heures of the Duke of Berry HERE.

For each of the twelve days of Christmas you could study one of the images—I suggest printing them on card stock—beginning with the month of January. You could think about, and plan for, how you might bring the agricultural cycle into your home and family life over the coming year. Children will enjoy finding little details in the pictures.

General themes for the Labors of the Months are:

- January: Feasting and celebrating

- February: Resting by the fire

- March: Pruning, plowing, and digging

- April: Planting, strolling, and picking flowers

- May: Maying and courting

- June: Haying and shearing sheep

- July: Harvesting wheat

- August: Threshing wheat

- September: Harvesting grapes

- October: Ploughing, sowing seeds, and winemaking

- November: Harvesting acorns to feed to pigs

- December: Butchering animals, hunting, and baking bread6

Wheel of the Year

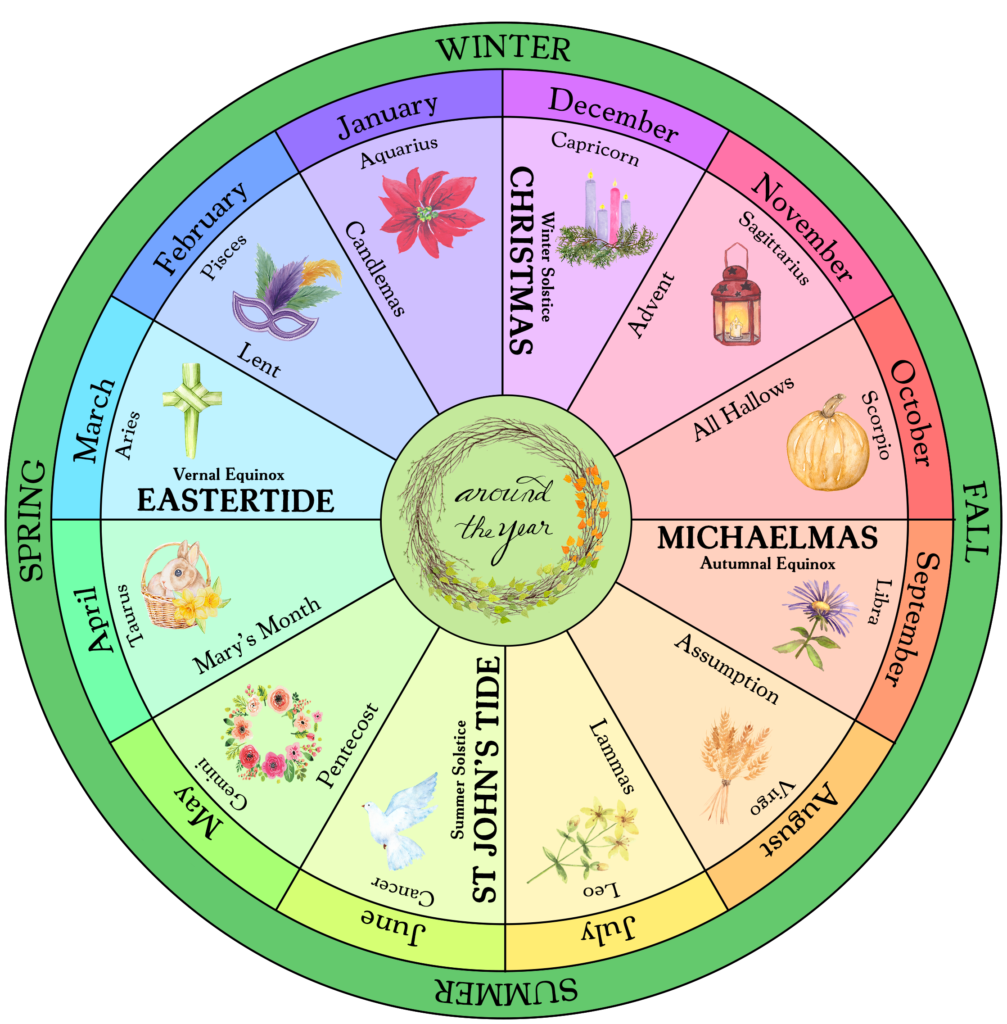

Create a Wheel of the Year for yourself, on which you can overlay ideas or plans for the coming months. I’ve created a blank template to get you started (download HERE), and it includes several important features:

- Labels for the seasons, months, and signs of the zodiac.

- A counter-clockwise orientation, which is how the progress of the year was visualized during the Middle Ages—it also mirrors how we experience the movement of the sun in the northern hemisphere (that is, east to west).

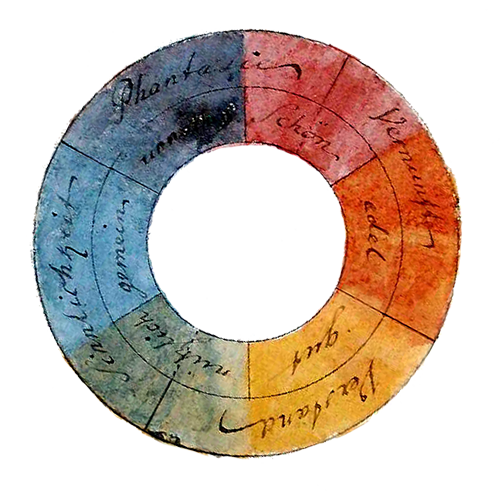

- Color-coded months, based on Goethe’s color wheel. Unlike Newton before him, who created an unbalanced color wheel with seven colors, Goethe designed his color circle with six colors and with an emphasis on both symmetry and complementarity. In making use of Goethe’s color circle as a visual representation of the year, one gets to experience this sense of balance and wholeness, and how the rhythms and seasons of the year complement one another. Below you can see Goethe’s depiction of the color circle, and my own Wheel of the Year. 7 8

ENDNOTES

1 Rudolf Steiner, Art as Seen in the Light of Mystery Wisdom, trans. P. Wehrle and J. Collis (E. Essex, UK: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2010), 74.

2 Maria Augusta von Trapp, Around the Year with the von Trapp Family (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2018), 67.

3 Benjamin Thorpe, Northern Mythology (London: Edward Lumley, 1851), 277-280.

4 Almut Bockemuhl, A Woman’s Path, trans. P. Wehrle (E. Essex, UK: Sophia Books, 2009), 58.

5 Clarck Drieshen, “The Medieval Christmas Weather Forecast,” Medieval Manuscripts (blog), December 19, 2020, https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2020/12/the-medieval-christmas-weather-forecast.html

6 Lisa L. Spangenberg, “Labors of the Months,” Scéla (blog), accessed December 10, 2021, https://www.digitalmedievalist.com/things/manuscripts/books-of-hours/labors-of-the-months/

7 Kevin Hughes, “Light Filled Color: Translucent Colors and Their Use in the Waldorf School,” Renewal 9, no. 1 (2000): 26.

8 Neil Ribe, “Exploratory Experimentation: Goethe, Land, and Color Theory,” Physics Today 55, no. 7 (2002): 43.